If I am forced to place these occupations into boxes, it's with reluctance, as I believe there are too many confusing crossovers. However, here are the simplest dictionary style definitions I could come up with to describe the differences:

Craftsperson: A skilled person who makes or repairs bespoke, as opposed to mass-produced, items that may be decorative but tend to be functional. The pattern or idea is usually provided by someone else. Textile crafts are extremely diverse and include quilting, spinning, dyeing, basketry, tailoring and methods of fabric production such as weaving, felting, hand-knotted carpets, needlepoint and knitting.

Designer-Maker: Self-explanatory and similar to a craftsperson but the template or idea is also their own.

Designer: Creates the pattern or idea for bespoke, or often mass-produced, textile items. Production is carried out elsewhere. Well-known textile designers include homeware and fashion designer Orla Kiely, and Amy Butler, who specialises in prints for home-sewing.

Artist: Creates works that may be functional, but are more concerned with aesthetics than utility. Textile artists incorporate fibres somehow.

However, there are no essential qualifications to give yourself any of these titles. A few weeks ago, I went to the contemporary visual art fair, Art in the Pen and as I picked up business cards, I noticed how exhibitors described themselves. I considered two exhibitors there. Both were using wet felting techniques to create items to hang on your wall, yet one, Angela Barrow, described herself as a 'Feltmaker', the other Valerie Wartelle, a 'Fibre Artist'. I liked both their work yet I felt that there was a difference here, above the obvious difference in inspiration and style. Not necessarily down to any level of skill, but according to the descriptions above, I would say Angela is a Designer Maker, whereas Valerie's work I felt was art. Partly I thought, I was influenced by how Valerie's work is viewed - framed and behind glass. (Often textile art is left unframed so that the textural qualities can be appreciated.) Valerie's work also is very painterly and though it's described as contemporary, it has traditional fine art qualities and subjects, portraying realistic, highly atmospheric landscapes. Her sewing machine needle has been used like a paintbrush. I found it aesthetically beautiful though it was really the level of expression I felt that made the difference.

|

| Artfelt by Valerie Wartelle's 'Earthlungs #4' 79cm x 34cm (Used with permission of the artist) |

By now I was questioning whether titles really matter. I've read cover to cover Kaffe Fassett's autobiography 'Dreaming in Colour' recently, as he is one of the textile artists I've chosen whose work inspires me. I've concluded, it is impossible to categorise someone like him, who simultaneously paints still life, illustrates, knits, does needlepoint and mosaic whilst designing fashion knits and quilting fabrics and I was relieved to read this refreshing quote:

"The distinction some purists draw between art and craft doesn't exist for me. So many artists today seem to be able to use textile making in their work that the barriers are softened. I always try to make my textiles as beautiful as I can manage imbuing them with all the efforts of a work of art. It's up to others to describe, if they have to, what it ends up being". (Fassett 2012:113)

(I particularly like the use of the word softened, which seems so appropriate for textiles.)

|

| Cover photo for 'Dreaming in Colour' Image courtesy of Kaffe Fassett Studio |

In his one man show in 1988 his exhibition at the V & A was the 2nd most successful in history, doubling the usual number of visitors, yet there was still negativity. 'Why is the great V & A stooping to have an exhibition of knitting patterns?' (Fassett, 2012:158) one newspaper asked. When a Rowan rep suggested he try patchwork in 1987, Kaffe himself said, 'isn't patchwork just cutting up old clothes and sewing them back together? (Fassett 2012:190). It's interesting to read that he found the prejudices towards textiles seemed to be greatest in the US, the home of the art quilt. While other countries clamoured for the exhibition on its world tour after the V & A, he was still struggling to get serious museum exhibitions there. Even in the '90s when he queried a curator, the telling answer came, 'We talk about you in museums in the US, but we feel you are too popular. But don't give up on us'! (Fassett 2012:195)

So it seems acceptance of textile art may vary by location. In Scandinavia, (Fassett, 2012:159) Kaffe suggests, it is perceived quite differently. Most people can sew, knit and embroider to a high standard. Although the techniques are simple and something everyone can do and can therefore relate to, they appreciate the worth in the excitement of the colour and texture combinations, harmony of placements and proportions. He describes in Stockholm how sympathetic curators, painted walls and gathered complimentary antiques from the archives while the public formed long queues to get in and how touching the tactile exhibits was quite normal.

As for describing Kaffe Fassett's work, it covers so many areas that here I've concentrated just on needlepoint and knitting.

Kaffe Fassett

Materials: Mainly wool with cotton, silk and mohair to provide a texture change.

Scale: Big and bold. Large scale patterns and large needlepoint panels.

|

| Suzani Wrap Image courtesy of Kaffe Fassett Studio |

|

| Lidiya Felted Tweed for Rowan Knitting Magazine 48 Image Courtesy of Kaffe Fassett Studios |

Colour: Unapologetic. From rich, intense reds, hot pink, blues, oranges, greens and yellows to lavenders, rust tones and everything in between. 'When in doubt, add twenty more colours.' (Fassett 1985:8) Colour Influences have included paintings by Odilon Redon, Piere Bonnard , Edouard Vuillard and Severin Roesen and places as diverse as New York rubbish piles, Scottish landscapes, the markets of Portobello Road, Gaudi's Barcelona, Hyde Park flower beds and lines of laundry in India. Kaffe pulled out of art school when they began to study colour theory seriously in a scientific way. He believes (Fassett 2012: 49), colour is instinctive and is learned by constant observation and playful exploration.

|

| 4 Large Flower Cushions at Ehrman Tapestry Image Courtesy of Kaffe Fassett Studios |

Imagery: Foliage and flowers, fruit and vegetables. Cabbages, auriculars, pansies and big blousy blooms like roses and peonies come to mind. Natural forms like shells feature and ceramics are a big influence as well as geometrics. Circles, stripes, chevrons, lattice, Islamic arches and stars are often seen in layered patterns. I was surprised and delighted to find out that he can still be inspired now by strong visual memories of experiences many years earlier.

|

| Shells Carpet at Ehrman Tapestry Image Courtesy of Kaffe Fassett Studios |

Sue Reno is the other textile artist whose work I chose to describe. I'd made a shortlist and the images of Sue's work drew me in, just like Kaffe Fassett's, by its vibrant colour, particularly the combination of reds and greens next to the cyanotype print indigo. Having recently done some basic sun print experiments, I was interested to see more of its possibilities on fabric. Finally, as Sue is one of the best known Art Quilters in the world I was interested to consider when a quilt becomes an art quilt. I imagined that a quilt artist would face additional challenges in altering perceptions of a quilt as something other than a functional object, particularly in the US with its strong domestic roots.

|

| My sun print experiments |

I watched this YouTube interview with Sue a couple of times and found out that Sue from a young age was making clothing and traditional quilts. It was interesting to hear how she made the move from a hobbyist crafter who needed an avenue for expression away from her day job as a carer, to a dedicated professional art quilter. When asked how, she simply said that she 'declared it'. The move was all about re-invention and a change in mind set, exploring her core processes further and deeper. Art was now her priority - a job, not play and she learned to be assertive and disciplined, taking her studio time and schedules seriously. She explains how the timing of her decision coincided with the start of the Internet explosion and social networking and how she took advantage of this by learning the technology to promote her work and connect to her audience.

Sue also gives good advice in the interview about considering the various locations to exhibit your work. Like Kaffe Fassett who found his most welcoming reception in Scandinavia, Sue also found that her work was accepted and 'fit' better in some places than others

When asked about how her art form is perceived, Sue talks about the need to educate in where fibre art has gone. She says she has been lucky, in that when she joined a group of artists working in different disciplines, none of them ever questioned her use of fibre. To them, it was just another medium like painting or sculpture. She says there is still the tendency for women in particular, to undervalue their work and discount their labour and talent. To price her work fairly, she keeps detailed records of her time and materials. One piece can take several hundred hours to design, cut and stitch. Despite being one of the most successful art quilters in the world, Sue still has an unrelated day job to make ends meet. (I wondered now whether Kaffe Fassett would have enjoyed the same success had he been born female. He says himself that he was a source of interest, even a 'freak' (Fassett 2012:143), partly because he was man who knits. For me though, alongside his talents, it is his optimistic engaging personality and the encouragement he gives in his teaching that is the draw, regardless of gender.)

I contacted Sue to ask her how she felt about the acceptability of textile art as a fine art medium and was delighted when she took the time to send me this reply:

'I submit work in a variety of venues, ranging from traditional quilt shows to fine craft venues to mixed media /all media exhibits at universities and mid-level museums. I find that my emphasis on good design, original content, and excellent craftsmanship is increasingly welcomed and rewarded. I think some of the bias against textiles and fiber arts as "women's work" is finally eroding, and it is an exciting time to be a fiber artist.'

Sue Reno

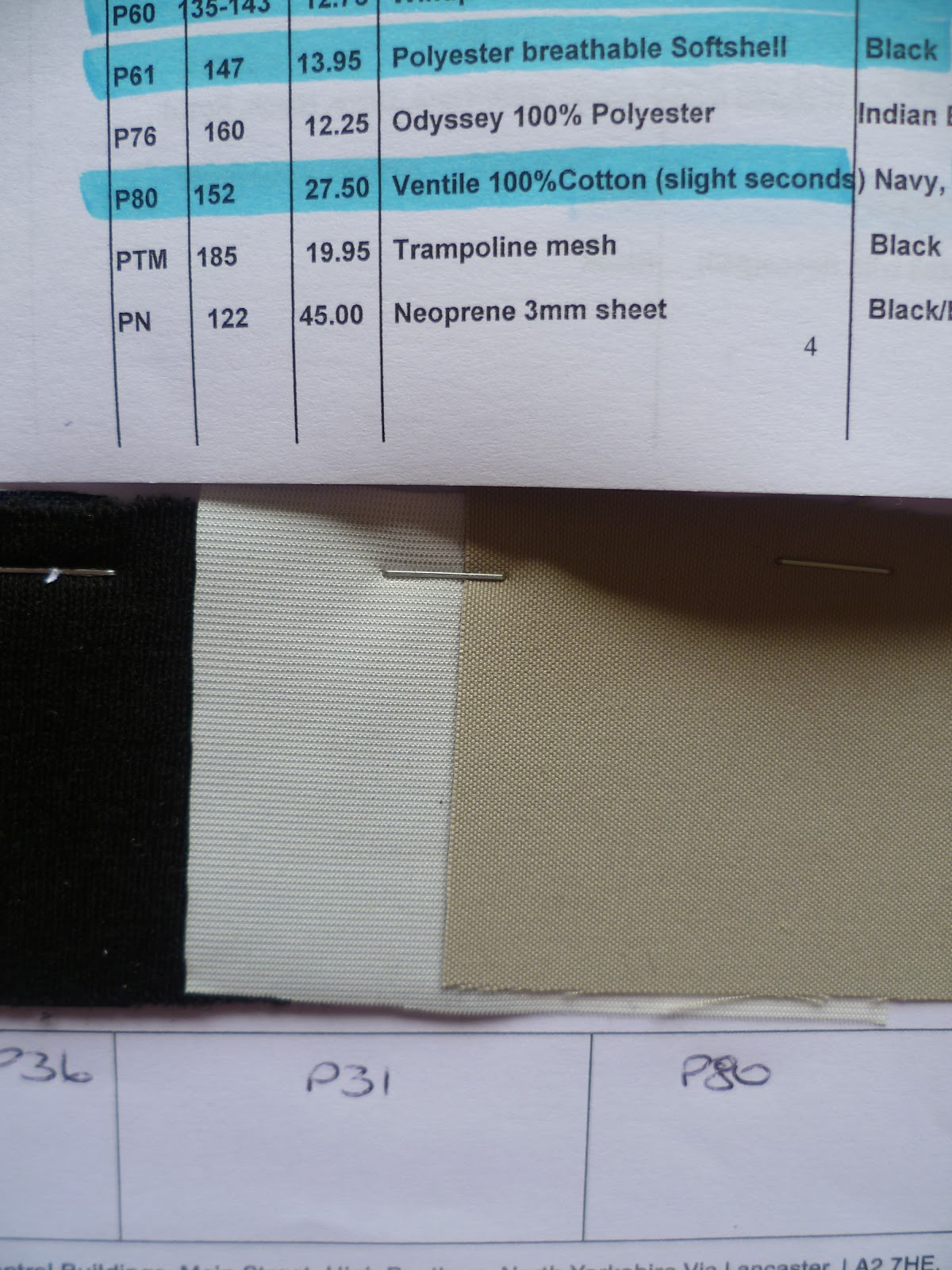

Materials: Indian silks, wools, cotton prints and recycled fabrics saved from decades of home dressmaking. Seldom buys fabrics - paints existing stash as necessary. Does buy PFD (prepared for dye) fabric from speciality suppliers like Whaleys (as mentioned in previous Research Point: Textile Diversity).

Scale: Prefers to make large scale, one-off, high end, labour intensive quilts for gallery exhibiting.

Techniques: Starts with the idea and colour scheme generated by photographs and collected subject material displayed on studio design wall. Uses Photoshop and digital printing directly onto fabric using freezer paper and archival ink. Also uses image transfer sun printing techniques on fabric (cyanotype and heliographic).

Components are prepared: 'Flip-and-stitch' technique is used to make foundation strips (similar to how I made background for my Roman Urn panel in Assignment 3 - Applied Fabric Techniques). Elements are combined by machine to create a surface cloth. Works quickly and intuitively using simple tools: a large table and a machine somewhere between a domestic and industrial model. Prefers the intimacy of a domestic machine but her model has a longer flat-bed allowing more room to manoeuvre the bulk of the quilt.

Cloth is layered with batting before depth, texture and movement is added with hand or machine stitch. Hand beading or fabric paint is sometimes applied if required.

|

| Ginger Cyanotype on Silk, Indian Silks and Machine Stitching Image used with permission of Sue Reno, all rights reserved |

|

| Fox and Hackberry Cyanotypes on cotton, monoprints on silk, artist painted fabric, commercial fabric, vintage crochet and stitching. Image used with permission of Sue Reno, all rights reserved |

Imagery: Architectural structures, flora and fauna (particularly skulls). Sue likes to hike, has an extensive organic garden and interprets her outdoor experiences - the leaves or glimpses of small mammals - into textiles.

|

| Silk Mill #3 Screen prints on cotton, digital images on silk, artist painted and commercial silk, cotton and wool fabrics, machine stitching. Image used with permission of Sue Reno, all rights reserved. |

Reading List:

Fassett, Kaffe (2012) Dreaming in colour: an autobiography. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang

Fassett, Kaffe (1985) Glorious knitting. London: Century Publishing

Hunt, Zoe & Fassett, Kaffe (1989) Family Album: knitting for children and adults. London: Guild Publishing